For years Māori and Pasifika peoples have suffered the impacts of inequities and disparities in health that manifest as greater incidence of ill health, poorer access to health and disability services and significantly poorer health outcomes.

- On average, Māori die seven years earlier than non-Māori and are 2.5 times more likely to die from diseases that can be addressed through health care.

- One-third of Māori preschool children receive no oral care, and more than half of 5-year-old Māori children have dental caries (33% higher than for non-Māori children).

- Young Māori have poorer general physical and mental health, are more overweight, have greater substance use, and higher exposure to violence.

- Hospital admissions for self-harm are higher and suicide rates double among Māori aged 15–24 compared to non-Māori.

- Māori develop diabetes up to 10 years younger and progress earlier to more serious disease, yet are less likely to receive appropriate monitoring and testing.

- Despite being significantly more likely to report multiple disabilities, Māori aged 65 and over are much more likely to have unmet need for a disability aid than non-Māori.

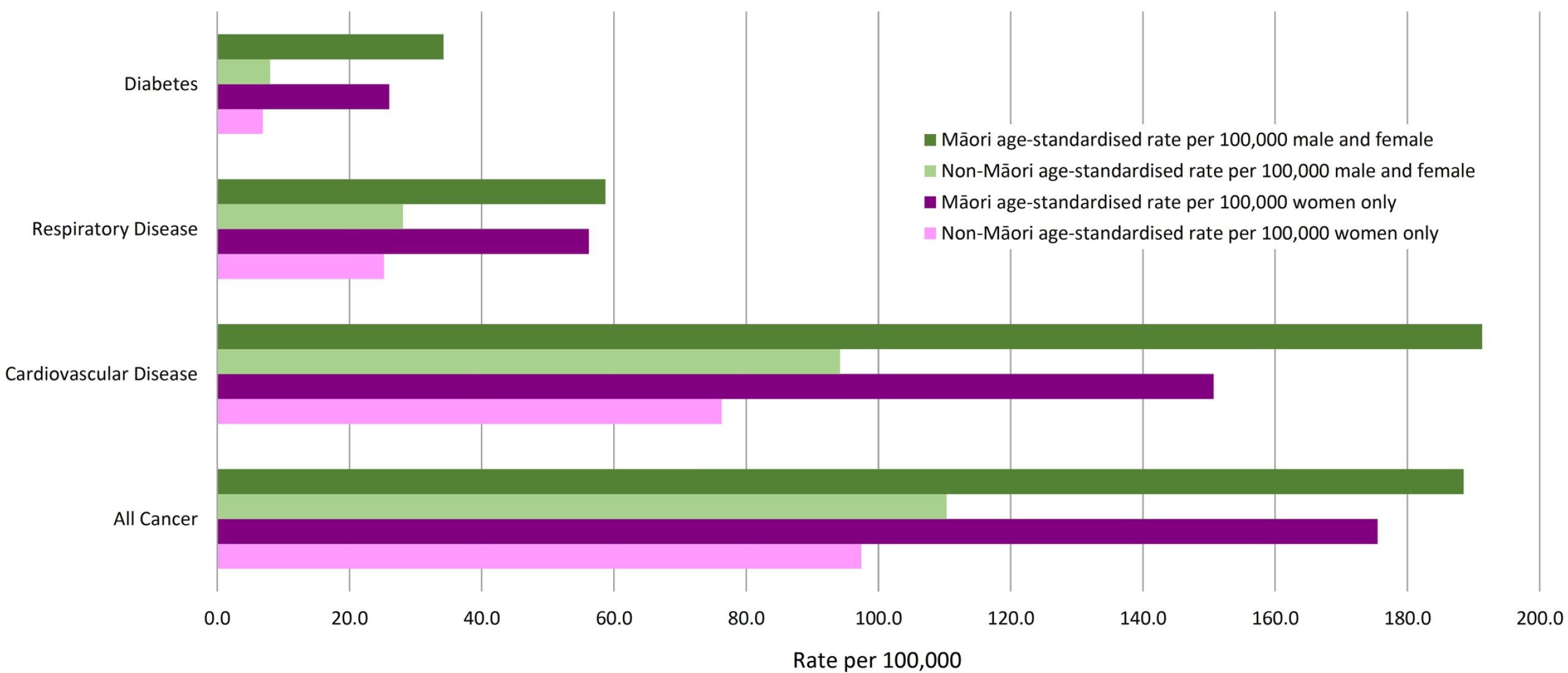

Figure 1 on provides the age-standardised death rate (per 100,000 of population) for Māori and non-Māori, women and total population for the four main non-communicable causes of death in 2016, showing clearly the disparities in outcomes for Māori.

Figure 1: Age standardised death rate (per 100,000 of population) for Māori and non-Māori, women and total population for the four main non-communicable causes of death in 2016 (from data from Mortality 2016: Data tables – MoH)

Even where “Māori are accessing health services, they do not always receive optimal quality of care, and this negatively affects outcomes for Māori. Lower quality of care includes suboptimal prescribing and over-prescribing to Māori, poor communication between professionals and Māori patients, delays in treatment and surgical interventions, and longer hospital bed stays after acute admissions.”

In July 2019, the report A Window on the Quality of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Health Care 2019 was published by the Health Quality & Safety Commission (HQSC). The report focuses on Māori health equity and concluded that there are the following health inequities for Māori:

- Inequity in access: services are less accessible for Māori, with health services being less likely to be accessible for Māori compared with non-Māori over the life course, beginning prior to birth,

- Inequity in quality: services are not providing the same benefits for Māori; even when they can access services, the evidence shows inequity in the quality of those health services and treatments for Māori.

- Improvement – efforts to improve quality do not always improve equity for Māori.

The Health and Disability System Review – Final Report found that there were higher rates of disability in families living in high deprivation communities and that Māori have significantly higher rates of disability across all age bands.

“Physically disabled adults experience a higher prevalence of chronic diseases including arthritis, asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and stroke,” and “people who have an intellectual disability have high levels of unmet health need.”

Mirfin-Veitch and Paris concluded in their review of primary health and disability that “for many disabled people, access to primary care is limited at the practice level through inaccessible premises, health information provided in inaccessible formats, and inexperienced health professionals.”

All New Zealanders must have easy access to equitable, affordable, accessible and available as well as culturally appropriate and acceptable health care when and where they need it. Addressing inequities and disparities in the provision of health and disability services must be the highest priority for the Government. No-one should receive a poorer level of care or have poorer outcomes based on ethnicity, culture, disability, level of deprivation or location of residence.

By Sue Claridge