Has the HDC Fulfilled Its Promise?

By Sue Claridge

Originally published in the April 2020 Auckland Women’s Health Council Newsletter

“The Health and Disability Commissioner promotes and protects people’s rights as set out in the Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights. This includes resolving complaints in a fair, timely, and effective way.”

~ HDC Website1

The passing of the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 and establishment of the role of Health and Disability Commissioner (HDC) was a direct response to the recommendations of the Cartwright Inquiry. Dame Silvia Cartwright recommended that the Human Rights Commission Act 1977 should be amended to provide for a statement of patients’ rights and the appointment of a Health Commissioner, whose role would include negotiation and mediation of complaints and grievances by patients, and heightening the health professionals’ understanding of patients’ rights.2

The establishment of the HDC and the implementation of The Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights (The Code), made law in 1996 by regulations, gave New Zealanders the impression that the sort of harm caused by Herbert Green and the “unfortunate experiment” and its cover-up would never happen again; that patients’ rights were protected; and there was a clear means for investigation and remedy through The Code and the HDC.

It was an entirely reasonable expectation. The Act and Code and the HDC were a promise to the New Zealand people that health and disability services providers would be held to account; that there would be fairness and justice applied in doing so. The Act promised “fair, simple, speedy, and efficient resolution of complaints”.3

Twenty-five years on from passing of the Act, appointment of the first Commissioner, and implementation of the Code, has the HDC fulfilled its promise?

Health and Disability Commissioner Act 19943

An Act to promote and protect the rights of health consumers and disability services consumers, and, in particular,—

(a) to secure the fair, simple, speedy, and efficient resolution of complaints relating to infringements of those rights; and

(b) to provide for the appointment of a Health and Disability Commissioner to investigate complaints against persons or bodies who provide health care or disability services; and to define the Commissioner’s functions and powers; and

(c) to provide for the establishment of a Health and Disability Services Consumer Advocacy Service; and

(d) to provide for the promulgation of a Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights; and

(e) to provide for matters incidental thereto

Many complainants describe protracted investigations of their complaints that take years to achieve resolution, while thousands of others lodge complaints only to find that their “cases” are closed without so much as an interview or follow-up. There is no right of appeal if your case is closed without further investigation or if you are unhappy with a decision, and under a no-fault system there is virtually no other way in which to obtain accountability for harms caused in health and disability services, no suing of health professionals for negligence or incompetence.

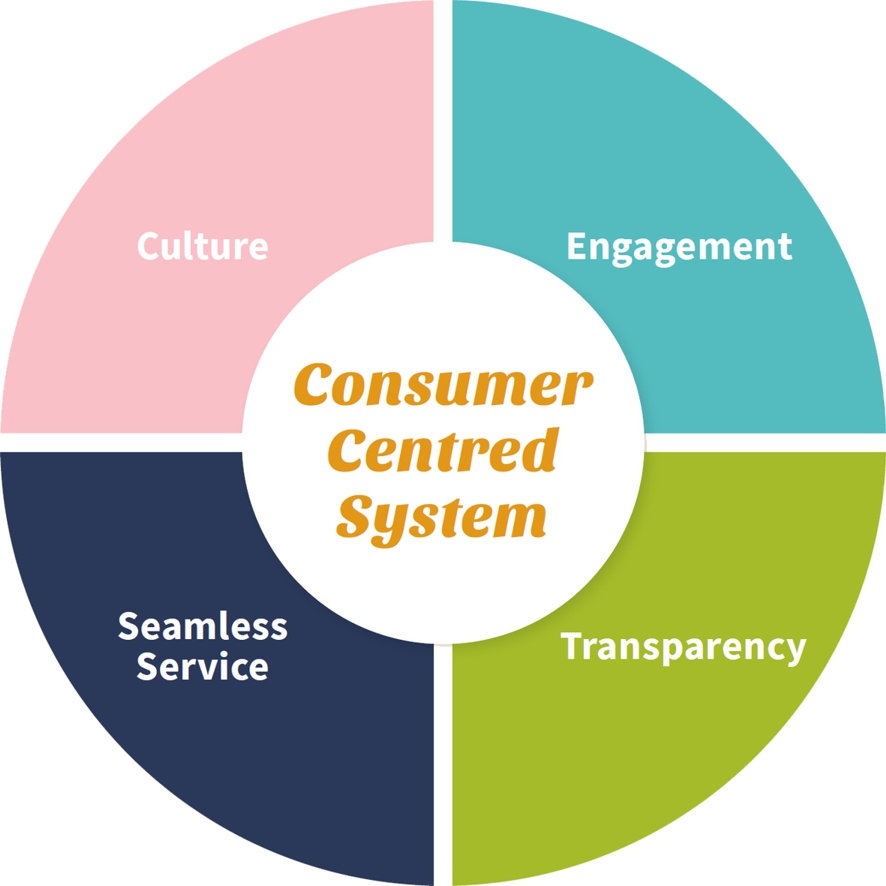

The HDC Annual report includes a graphic on its second page that has a Consumer Centred System at its core, surrounded by the ideals of culture, engagement, transparency and seamless service.

It’s not clear whether this refers to the HDC and the way in which it works, or our health system. Either way, it is aspirational, because this is certainly not what we have in either of them.

Few Complaints are Actually Investigated

The HDC was set up to protect the rights of New Zealanders in the health system; it is the only agency to which people can turn when something has gone wrong.

In his foreword to his 2019 Annual Report, Commissioner Anthony Hill talks of “closing” complaints. This would suggest to many readers that there has been resolution of these complaints, that there is some sort of closure or outcome for complainants, but the reality is very different. In the vast majority of complaints, the HDC’s decision is to take ‘no further action’ on the complaint after receipt and preliminary inquiry into it. Between 2014 and 2017 the HDC decided to take no further action in 55% of complaints received, approximately 1,072 of the approximately 2,000 complaints received per annum.4

Law professor, Jo Manning, told North & South that the fact that only about 4% of complaints lead to a formal investigation “attests to heavy emphasis on simple, speedy and efficient resolution. It is open to question whether this has been at the expense of fairness and whether the pendulum has swung too far in denying complainants access to the process given that they have no alternative avenue for resolution.”9

Others have noted the decline in investigations undertaken. In 2011, in an article in Medical Law Review, Prof. Peter Skegg wrote that investigations “declined markedly after the HDC Amendment Act 2003 came into force, and continues to decline.”5

In 2015, Stuart McClennan, a researcher in biomedical ethics, wrote that the continuing low number of HDC investigations were a cause for concern.6 He detailed the number of closed complaints versus the number of investigations every year from the year ended June 2001 to the year ended June 2012, with data from the HDC’s annual reports.

Bringing Stuart McLennan’s data to up to date, we see that the trend has not improved (see table below).

Stuart McClennan wrote that: “The low amount of investigations being carried out raises concerns that access to HDC investigations has become too restricted. The 2009 HDC satisfaction survey also found that one reason for complainants’ dissatisfaction with the HDC process was being denied an investigation.”6

He concluded that, while formal investigation not always be the most appropriate way to handle a complaint, the current amount of investigations being conducted was concerning and required further examination.

Four years on nothing has changed.

Table 1 Relative number of investigations as a proportion of complaints closed.

| Year Ended 30 June | Complaints closed | Investigations closed | Investigations as a proportion of closed cases |

| 2001 | 1338 | 538 | 40% |

| 2002 | 1299 | 234 | 18% |

| 2003 | 1338 | 345 | 26% |

| 2004 | 1162 | 178 | 15% |

| 2005 | 1158 | 172 | 15% |

| 2006 | 1110 | 116 | 10% |

| 2007 | 1273 | 89 | 7% |

| 2008 | 1295 | 100 | 8% |

| 2009 | 1378 | 112 | 8% |

| 2010 | 1524 | 51 | 3% |

| 2011 | 1355 | 27 | 2% |

| 2012 | 1380 | 44 | 3% |

| 2013 | 1551 | 60 | 4% |

| 2014 | 1901 | 115 | 6% |

| 2015 | 1910 | 100 | 5% |

| 2016 | 2007 | 80 | 4% |

| 2017 | 2015 | 80 | 4% |

| 2018 | 2315 | 102 | 4% |

| 2019 | 2392 | 102 | 4% |

Source: McLennan (2015)6; HDC (2019)7 and various other HDC annual reports8

Even if all of the increase in complaints lodged could be regarded as not meriting further investigation, investigated complaints as a proportion of closed cases has dropped significantly from 40% in 2001 to under 5% in 2019.

In her New Zealand Law Review article, Jo Manning says that “Once made, a complainant loses control over the handling of their complaint… The Commissioner’s choice of complaint resolution option is discretionary, with no relevant criteria attached, albeit subject to the Act’s purposes.”4

Most complainants who receive a ‘no further action’ decision are stuck with it. Unless the complainant is able to produce new and compelling information or evidence, the HDC is very unlikely to revisit their assessment.4

Delays in Complaint Resolution

The “wheels” of the HDC turn very slowly.

“Resolution times for both preliminary assessments and investigations can be lengthy, typically involving two to three years,”4 writes Jo Manning, which is as long as, if not longer than a civil action in our courts.4

A Sunday (TV1, Sunday 19 April 2020) investigation into the workings of the HDC complaints process found that it may take years of families doing their own research to uncover what has happened to loved ones injured in the medical system, leaving “kiwi families adrift in a system that is meant to be protecting them.”

In one case, a family has spent years working out for themselves what went wrong in the case of their premature, brain damaged daughter’s death. Andrea Donaldson, herself a health professional and PhD in Biochemistry and Forensic Science, undertook effectively a forensic examination of her own medical records to work out what went wrong when she gave birth to their daughter. What do those without this sort of training and skills and financial wherewithal do when something goes wrong? The Waikato DHB made a ‘Clayton’s’ apology, saying “sorry for your loss”, but there has not accepted responsibility.

The average time for the HDC to deal with maternity complaints is more than two years, but they have been investigating Andrea Donaldson’s complaint for more than three years. She is still waiting for the HDC report, while ACC has already completed theirs.

Anthony Hill, told Sunday: “in my view three years is too long, and I do I regret that, I think it is unacceptable.” But there are few signs that anything is changing to improve the process for New Zealanders.

Tim Lawn spoke to Sunday about his daughter’s brain damage as a result of her mishandled birth and their complaint to HDC. He said: “you just lose a lot of hope throughout the whole process.” His family’s complaint took seven and a half years to resolve, including a two and a half year HDC investigation. Despite a damning report by the HDC that found 14 breaches in the maternity care provided, the Lawn family faced a further five-year fight for compensation and acceptance of responsibility by the DHB.

Jo Manning told North & South that the HDC quickly “resolves” cases by taking no further action, and that when investigations are undertaken, it “publishes less information on resolution times than it did before and key dates are no longer included it its reports.”9

“The last two tactics are surely intended to shield the office from criticism for delays,”9 she says.

Effecting Change?

It would not be unreasonable to expect that, over time, if the HDC was effective, the relative proportion of complaints (i.e. per capita or relative to the number of interactions with health and disability service providers) would decrease.

“Commissioner Hill told North & South that “consumers say to us that they don’t want this to happen to anyone else. They want the system to improve.”9 He claimed that the way in which the complaints system operates brings change in the health system that improves performance.

In an analysis of complaints presented in a session at the HDC Conference in November 2017,10 the presenters revealed that those at increased risk of complaints were:

-

-

- male*,

- general practitioners,

- vocationally registered, and

- had been in practice for 21-30 years.

-

Australian research, highly likely to be reproducible here, has found complaints clustered heavily among a small group of doctors. Approximately 3% of practicing doctors accounted for half of all complaints. The greater the number of prior complaints doctors had experienced, the greater their short-term risk of further complaints.11

No Right of Appeal – A Denial of Natural Justice

If your ACC claim is denied, you can appeal.† If you are convicted of a criminal offence, you can appeal. If an Employment Relations Authority decision goes against you, you can challenge it through the Employment Court. If you lodge a complaint with the HDC and the HDC takes no further action, refuses to investigate, or the investigation does not uphold your complaint or the resolution is unsatisfactory you can, well, do nothing. There is no right of appeal and there is no ability in New Zealand to take a medical negligence action for damages.4

Jo Manning writes:

“…the governing legislation does not provide an appeal or review mechanism, … it gives the Commissioner broad, largely unreviewable powers to control the fate of complaints. The HDC complaints process is the only available option for aggrieved patients and their families to have their grievances substantively addressed; there is no alternative means of doing so. The HDC complaints process is virtually the “only game in town” for complainants. Yet they cannot access it as of right, nor can either party seek to correct decisions they consider wrong or unjust.”4

The lack of right to appeal is equally applied – health and disability service providers also have no avenue to appeal a decision that goes against them.4

Jo Manning says that the only option if you are dissatisfied with the HDC’s response is to “seek an internal review, a prohibitively expensive judicial review or make a complaint to the Ombudsman.”9 However, with the Ombudsman or a judicial review, only procedural unfairness and errors of law will be considered, not the merits or fairness of the decision itself.9

Even then, the most the Ombudsman can do is refer the complaint back to the Commissioner, enabling him to reconfirm his original decision.4

In comparing the generous rights of appeal on ACC decisions with the striking “lack of any opportunity for external review or appeal from adverse HDC decisions”, Jo Manning says that the difference between the two is indefensible.4

One of Jo Manning’s significant concerns is that if there are high levels of dissatisfied complainants, there is the risk that they will boycott the complaints regime.4 Thus, providers who breach patient rights are never held to account and their shortcomings are never brought to light. In such an environment, Commissioner Hill’s claim that the complaints system will bring change in the health system and improve performance is no longer valid.

Among a number of remedies to the current situation, Jo Manning advocates for an external review or appeal process, saying that while “the finality of the process is consistent with the simple, speedy, and efficient aim of the legislation… [it] compromises the ability to achieve fair outcomes too much.”4

Surgical Mesh and the HDC Response

Surgical mesh arguably represents the most serious medical injury crisis New Zealand has experienced in the last twenty or more years. Yet, the HDC, who should have been there to protect, and advocate for the vulnerable patients harmed by mesh procedures, has been remarkably absent from attempts to address, repair and ameliorate the damage.

According to the report on the surgical mesh restorative justice process held in 2019, there were only 45 complaints to the HDC relating to surgical mesh in the four years to June 2019.12

In her Bachelor of Laws Honours Dissertation, Jade du Preez found that, “Despite articles and submissions indicating mesh-related complaints to the HDC, a website search of HDC decisions concerned with problems from the use of mesh yielded only 3 results, and all of these were in relation to hernia repair.”13

In August 2018 a Medsafe report found that more than 1000 people have reported issues with surgical mesh.14 ACC received over 1018 treatment injury claims between 2005 and June 2018, of which 771 claims were accepted. Hernia repair accounted for 271 accepted claims and pelvic organ prolapse and/or stress urinary incontinence repair accounted for 453 accepted claims.15

So, why have so many of the hundreds of women devastatingly damaged by pelvic mesh devices failed to complain and why were only three of the 45 complaints upheld – all of them relating to hernia repair?

In her research, Jade du Preez found that mesh injured New Zealanders were frustrated in their attempts to complain via the HDC process.13

The report on the surgical mesh restorative justice process further detailed the mesh patients’ frustration and disillusionment with the HDC process:

The HDC was frequently described as “not upholding my rights”. Participants stated there was “no point” in pursuing the HDC process as the mesh community knows “they don’t do anything”.

The report said that patients who had experienced an HDC investigation found it deeply distressing, and those who had complained that their right to make an informed choice and give informed consent had been breached were told, ‘I had informed consent because I signed the form.’”12

Many wanted “the HDC to step up, encourage people to make complaints and actually act on them in the patient’s interest”.12

Mesh Down Under co-founder, Charlotte Korte, has been appalled by the HDC response to the restorative justice process and the request that they participate.16 The HDC claimed that the decision not to participate was in order to remain completely impartial. The HDC were the only agency who chose not to attend a listening circle (ACC, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Royal Australia & New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners and the Medical Council all attended). This supposed impartiality is seen as a frequent excuse for a lack of engagement.

Charlotte Korte says that the HDC chose to only ‘promote the visibility’ of their advocacy service, a service that people are unwilling to use because of their cynicism towards the organisation. She reiterates the restorative justice report, saying that “the majority see laying a complaint as waste of time, and a fruitless exercise. Those that have complained have found the process extremely distressing, because in many cases the ineffective complaints process leads to patients having to do their own investigation. The mistrust of this organisation’s ability to uphold patients’ rights is clearly evident.”16

How is it possible to reconcile the stated purpose and duty of the HDC – to promote and protect the rights of consumers – with the HDC’s incredible “hands off” approach to dealing with the devastation wrought by surgical mesh?

Commissioner Anthony Hill did respond to the criticism levelled at his office and the complaints process, saying “HDC will take on the feedback we have heard in the report about our complaints process”, but then went on to promote the National Advocacy Service, without addressing the distress and frustration that patients experienced with the complaints process.17 Nor did he address the HDC’s refusal to participate in the Listening Circles in which other agencies participated.

Conclusion

Given the evidence, it appears that the HDC’s resolution of complaints is neither fair, timely, or effective. In addition, there is scant evidence, if any, that there has been any change in the culture or system, or a shift in focus to the patient or consumer. As a result, the HDC is not fulfilling its “promise” to promote and protect the rights of consumers.

The AWHC has previously expressed its concerns in several fora, and including directly to the Minister of Health, about the inadequacy of the HDC in fulfilling its purpose to protect consumers and respond appropriately and in a timely manner when their rights have been breached.

After ten years as Commissioner, with a second term in the position (which was to end in July 2018) and an extension to his tenure, Anthony Hill will leave the role this year.18

We have expressed to the Minister of Health our hope that the new Commissioner will bring fresh insights and different expertise and experience to the role. After periods (since 2000) during which male appointees have occupied the role, we also hope serious consideration will be given to appointing a woman. We have no insight into the current process of recruiting and appointing the new Commissioner, and at the time of writing, the global Covid-19 pandemic will no doubt have forced this process down the list of the Minister’s priorities. However, given the ongoing importance of the role, we hope that it will be publicly advertised, and that a thorough search will be conducted to ensure a strong field.

* Even when correcting for the number of males in practice versus females, male providers were far more likely to be the subject of a complaint to the HDC than female providers. Approximately 75% of complaints were about male doctors while they make up only about 60% of doctors in the workforce.

† In fact, there are multiple levels of appeal against ACC decisions all the way to the High Court and Court of Appeal.4

References

- HDC website: About Us page

- Cartwright SR, 1988: The Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Allegations of the Treatment of Cervical Cancer at National Women’s Hospital and into Other Related Matters, Government Printing Office.

- 1994 Health and Disability Commissioner Act

- Manning J, 2018: “Fair, Simple, Speedy and Efficient”? Barriers to Access to Justice in the Health and Disability Commissioner’s Complaints Process in New Zealand, New Zealand Law Review, 2018 Issue 4.

- Skegg PD, 2001: A fortunate experiment? New Zealand’s experience with a legislated code of patients’ rights, Medical Law Review, 2011 Spring;19(2):235-66.

- McClennan S, 2015: Low yearly completion rate of HDC investigations is a cause for concern, New Zealand Medical Journal, 15 February 2013, Vol 126 No 1369

- HDC, 2019: Health and Disability Commissioner Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2019, Health and Disability Commissioner, Auckland

- HDC Annual Reports searchable by year

- Chisholm D, 2019: New Zealand’s Bitter Pill, North & South, July 2019.

- King J and Davidson N, 2017: HDC Complaint Data: Patterns and Predictions, HDC Conference, 13 November 2017.

- Bismark M et al., 2013: Identification of doctors at risk of recurrent complaints: a national study of healthcare complaints in Australia, BMJ Quality and Safety 2013 Oct; 22(10):879-80.

- Wailling J, Marshall C & Wilkinson J, 2019: Hearing and responding to the stories of survivors of surgical mesh: Ngā kōrero a ngā mōrehu – he urupare, A report for the Ministry of Health. Wellington, New Zealand: The Diana Unwin Chair in Restorative Justice, Victoria University of Wellington.

- du Preez J, 2018: Developing New Zealand Regulation: Lessons from Pelvic Mesh Devices, unpublished Bachelor of Laws Dissertation, University of Auckland.

- MoH, 2018: Adverse Event Reports Relating to Surgical Mesh Implants: Summary of data received by Medsafe, August 2018.

- ACC, 2018: ACC Treatment Injury Claims Surgical Mesh-Related Claim Data From 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2018, ACC 31 October 2018.

- Pers Comm. April 2020 from Charlotte Korte, Mesh Down Under.

- HDC Website: Media Release: Response to release of surgical mesh report

- HDC Website: Media Release: Commissioner moving on from HDC after a decade

Complainants Feel the HDC is Weighted in Favour of

Health Professionals

In an investigative article for North & South, journalist Donna Chisholm spoke to families who felt let down by the HDC and the complaints process. Kaya Miller died from a metabolic brain disorder after his diagnosis was delayed when an opthamologist – who believed that eight-year old Kaya was making up his symptoms, including near blindness – did not refer him to a neurologist urgently. A more timely response by the ophthamologist could have saved Kaya. His mother, Vicky Gibson, lodged a complaint with the HDC, but it closed Kaya’s case without further action or investigation; she says that “it feels absolutely that [the system is] in favour of doctors and you are constantly up against it.”9